James and Arizona's 160-year-old Law

In this mirror, our national failures are closer than they appear

“Where am I?” I asked.

“You’re in Illinois,” the old man said.

“So, I’m in a free state?”

The men laughed. “Boy, you’re in America.” –Jim and Old George in Percival Everett’s James

As the humble keeper of this book saloon, I spent last week visiting the 1860s courtesy of Percival Everett’s James. It retells The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of enslaved Jim and was one of my March book recommendations.

I had been working on a post about it, in celebration of National Library Week (April 7-13), placing James in the context of current debates about the freedom to read and Toni Morrison’s 1996 introduction to Twain’s classic, which dismisses attempts to ban the book as an “elementary kind of censorship designed to appease adults rather than educate children.” Delighting in Everett’s ironic and optimistic take on attempts to ban books—he believes they stop only those who won’t read anyway, and can never stop art.

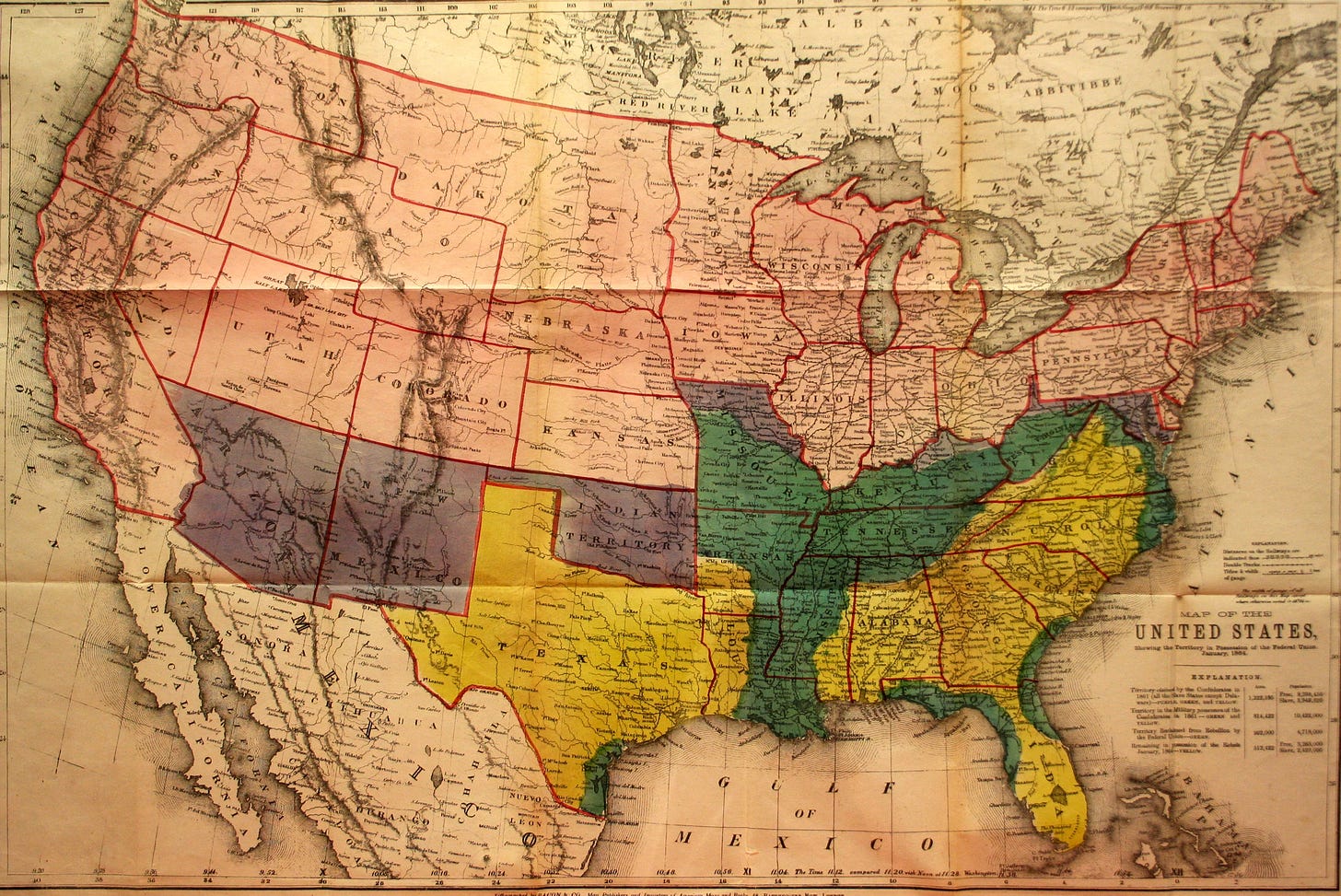

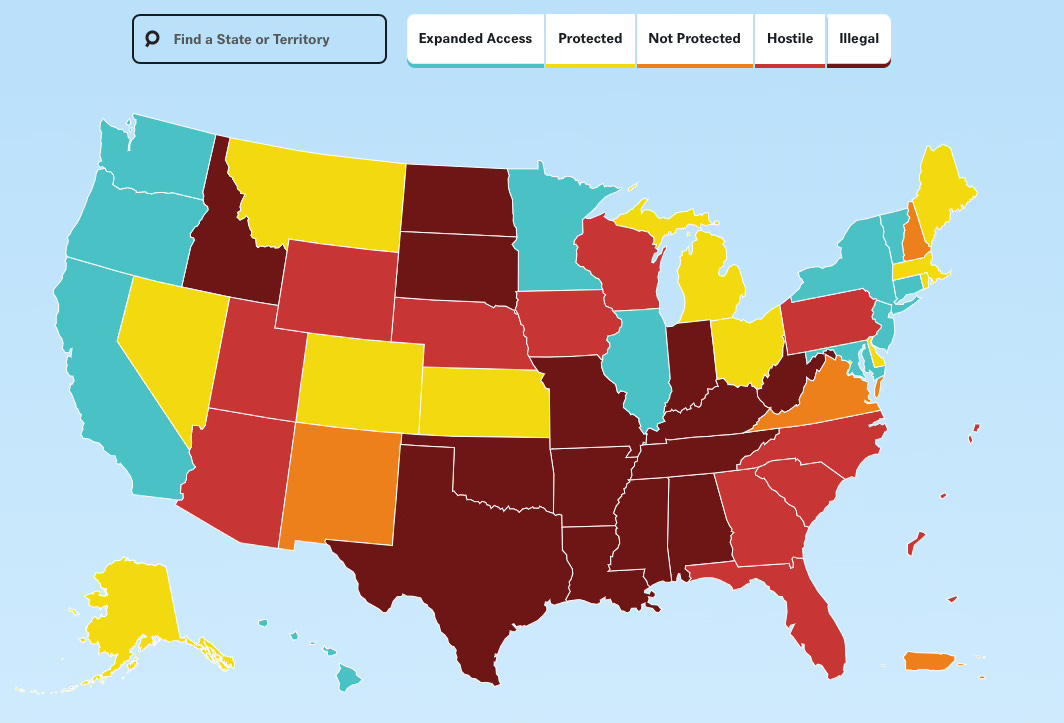

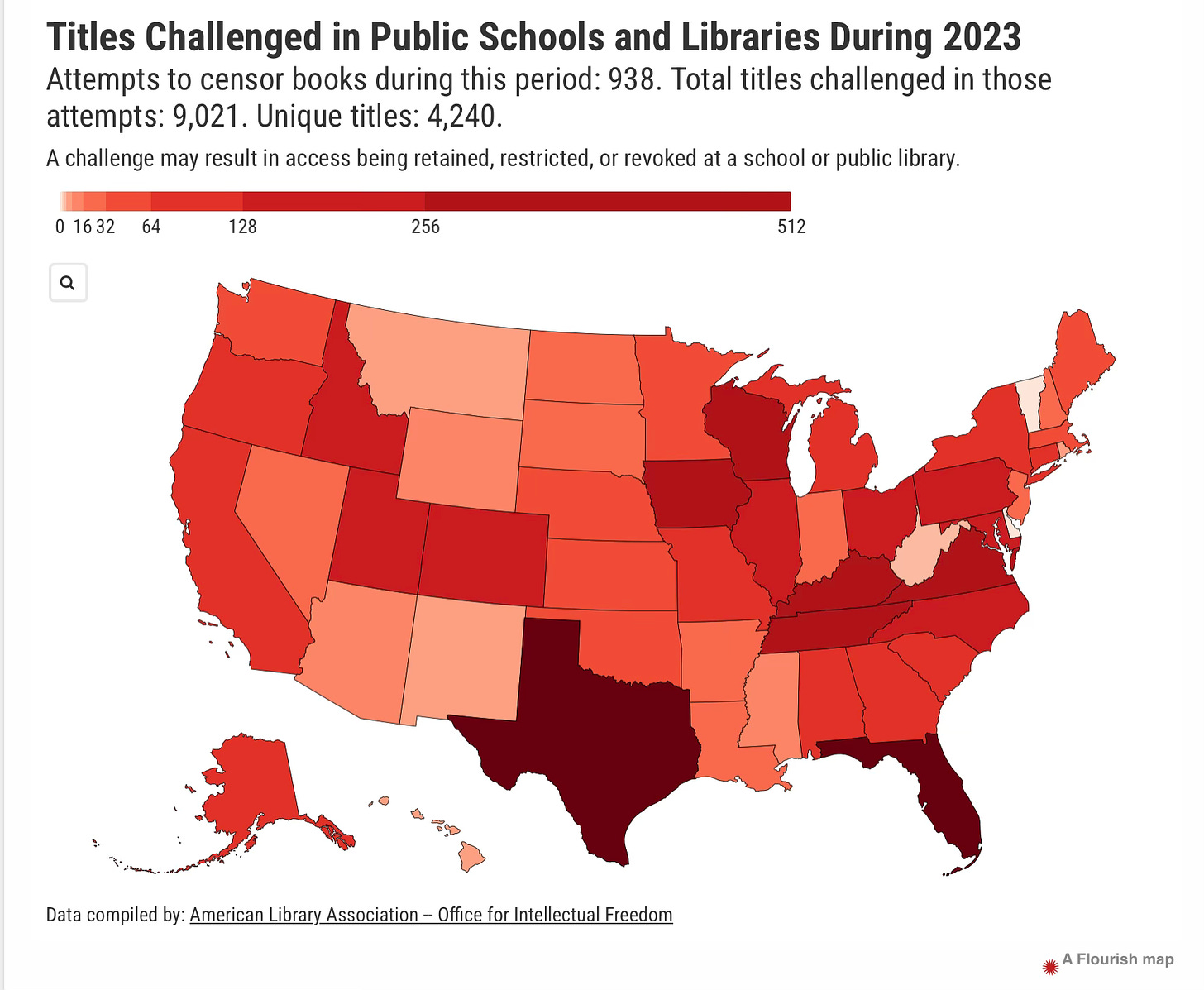

Deciding which map of national book challenges to include.

Then last Wednesday, the state Supreme Court determined an Arizona territorial statute from 1864 criminalizing nearly all abortion with the penalty of 2-5 years in prison will become the law in the next 14 days. This gave me a severe case of the Oscar Wildes.

For the rest of the week, every time I tried to write about James, I thought about the Arizona decision. And every time I thought about the Arizona decision, I found myself thinking about James.

At first, I resisted this impulse to draw on Everett’s book to comprehend the palpable alarm I felt at the Arizona decision. Yes, James takes place within 3-4 years of when the 1864 Arizona law was written. But also: James is fundamentally the story of two runaways, one an enslaved man and one a free child, and the relationship they forge in defiance of the rules propping up America’s original sin of slavery.

Yet the book’s related themes kept tugging at my mind: family building, self-determination, the farce of a nation that carves out zones of autonomy for some and not others with invisible state lines. I began to pull the threads of these thoughts together to share what I found.

To be clear: I am not suggesting in this piece that the condition of a being a woman in Arizona under this law is akin to being a slave in Missouri in 1861. That would be historically and morally incorrect and offensive. I am suggesting USA 2024 is not as different from USA 1864 as we might want to believe. In this convex fictional mirror, our deepest national failures to coherently understand and protect human rights are revealed to be closer than they might appear.

We know Twain’s work for its use of sardonic humor to point out contradictions of power and morality. In James and his other work, Everett also exploits irony to amuse and jostle the reader’s awareness. As Cord Jefferson explained to The Daily Show, this ability to give people permission to laugh at the absurdity of racial dynamics motivated him to adapt Everett’s Erasure for the screen.

In recent days I’ve similarly enjoyed

’s on “Some Other Things Women Were Not Able to Do 160 Years Ago” and “Some Recipes to Make For When You Lose Your Bodily Autonomy.” The silly jokes about Kari Lake other people in power who lie in ’s Dingus of the Week feature on helped release stabby feelings through recognition and laughter.What I like about these pieces: they find humor in undermining the folks in power. It’s too easy to mock Arizonans instead, as Stephen Colbert did on The Late Show, as though this development were a sign of something wrong with the people here rather than a perversion of the powers governing us all. Gesturing with cowboy finger guns Colbert said, “Giddyup pardner. Yesterday, Arizona reinstated a 160-year-old abortion ban. That is crazy. But it’s Arizona, so it’s a dry crazy.” But it would be a mistake to consider what’s happening in Arizona anything other than a classic American story.

The timeline for how this law came to replace a measure restricting abortions after 15 weeks signed by the state’s former Republican governor in 2022 twists like the Mississippi river, as anti-romantic and chaotic as a Mark Twain novel. Dianna M. Náñez of Arizona Luminaria gives a good rundown of how our rights were swallowed by this dark undertow, caught in the eddy of the U.S. Supreme Court Dobbs decision and an activist state attorney general.

In addition to late night TV sendups, you might also be enjoying the national newspaper takedowns focused on the Dauphin-like character William Claude Jones. Jones, who in his 40s and 50s married and left a series of wives before they’d be old enough to get a driver’s license today, headed up Arizona’s first territorial legislative assembly when it first approved the 1864 law. In addition to penalizing use of agents or instruments to bring on “miscarriage,”it also established the penalty for engaging in sex with females younger than age 10 (even if the child had given whatever amounted to “consent” in those days).

In Twain’s novel, the misery of unchecked mid-19th century parental neglect and abuse drives Huck into exile. Though Twain’s novels are known for their exaggerated sardonic qualities, this was likely not overly dramatized. In both the original and in James, Jim’s fatherly role tempers the shock of his vulnerability. Everett does something wonderful with this dynamic, making James the unequivocal agent in this relationship, rather than the default “father for free” described in Morrison’s 1996 introduction to the troubling original.

Jones’ notoriety as a reflection of the lack of protections of wanted or unwanted children in those days allows us to imagine (and shudder at) yet another possible rewrite of the story featuring Huck as a neglected 1860s girl who might be chosen by someone three decades older for a wifely rather than daughterly role. But it’s important to note that Jones didn’t write this 1864 law.

reminds us in her April 9 post that Judge William Howell, who single-handedly wrote the Howell code, was a New Yorker who’d been in the territory a matter of weeks. He was commissioned by President Abraham Lincoln to ensure Arizona would be established free from slavery. As Richardson emphasizes, the tone of the code is less concerned with managing the agency of women, but rather with controlling the conduct of the settler men who would establish the territory The aspect of the code relevant to modern day abortion is embedded in a section on “Poisoning.”Sarah Handley-Cousins blogged in 2016 for the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, about the use of herbs, in consultation with midwives and community healers, to bring on menses absent fetal movement. Restoring menstruation through the use of pennyroyal, tansy, cotton root or other available plant-based remedies was practiced knowlingly without incident for centuries.

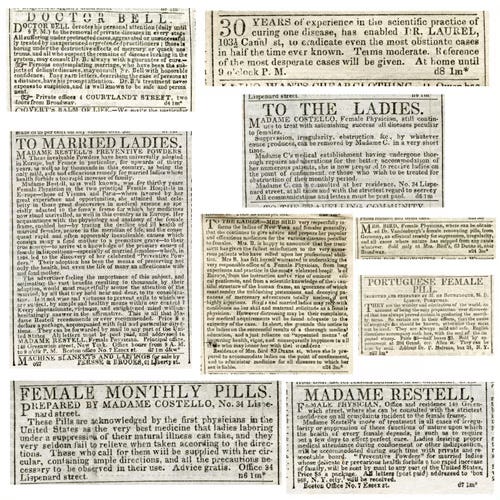

In the early to mid-19th century, these remedies began to be commercialized. Ads for pills and consultations ran in newspapers, their language reaching women concerned about “stoppage” of their menses without ever using the words mother, child or abortion at all. According to historians, the seeds of the current U.S. abortion laws were meant to regulate the commercialization of these services and remedies and their potential to do harm to women, rather than to restrict the private act of ending an early term pregnancy itself.

As Everett has explained in several interviews about his book, James is ultimately about language. Through elaborate code switching, the characters develop their own meanings and rhythms to communicate with and protect each other without their oppressors having access to their messages. Rooted in the characters’ quest to live as full human beings despite the real fear of the harm enslavers might inflict, James’s command of both languages reveals the enslavers’ fear of communication—and community—among those they controlled.

Researchers have spotted similar patterns in these ads for abortifacents and services. Handley-Cousins and others draw a line from enslavers practices straight through the post-Civil War era and our current abortion landscape. In James and every other slave narrative I can think of, enslavers do not consider their use of enslaved women’s bodies to be rape. They profited from resulting pregnancies. Handley-Cousins connects the dots between nascent anti-abortion efforts and enslavers concerns about Black midwives interfering in their cruel practices. As the Civil War shifted in favor of the Union, bringing Blacks increasing freedom to live as autonomous families and leading the U.S. to invite more immigrant labor, a “replacement theory”-based fear of declining births to White women drove a desire to also limit White women’s access to commercially available remedies and the midwives familiar with home remedies. Legal strategies began to encode pregnancy—and abortion—as a question not only of moral perogative and family building, but of duty and crime against the state.

A desire to preserve his family units drives much of James’s decision making in Everett’s novel. But the fugitive slave laws also conscribe the route he and Huck take to that desired goal. They’re the reason why James doesn’t make a beeline from Missouri to Illinois, a supposedly free state, knowing bounty hunters pose a risk no matter which side of the invisible line he stands on.

The first observation I could find of the parallel between the mid-19th century fugitive slave laws and the effect of today’s interstate legal quagmire ensnaring abortion seekers and providers comes from Richard Blackett, a retired professor of abolitionist history at Vanderbilt. Blackett told NPR in 2021 that while watching a TV news segment about the penalties provided for in Texas’ post-Dobbs abortion law, he said to his wife, “this sounds like the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.” That law made bounty hunters eligible for federal cash payments for turning in fugitives and those who harbored them, while also making even abolitionists in free states vulnerable to suits and fines in cases where they did not reveal fugitives or those aiding them. In 2022, Business reporter

also covered this connection for the LA Times.More recently, a 2024 University of Pennsylvania Law Review article “Conflicts of Law and the Abortion War Between the States” builds upon this observation. “On the subject of abortion, the so-called ‘United’ States of America are becoming more disunited than ever… [partisan and geographic divisions precipitated by the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision] create perhaps the biggest set of nationwide conflicts of law problems since the era of the Fugitive Slave Act before the Civil War.”

An example of collaboration between three clinics within 20 minutes of each other near the Missouri/Illinois border—the same area where James and Huck dodge minstrels and hucksters and bounty hunters—features prominently in their analysis of the legal conflicts created by the division between states. Like Texas, Missouri state legislature subsequently voted to criminalize the provision of abortion to Missouri state residents beyond their state’s borders.

This reality sparked the online backlash against Fox Business guest Mark Simone’s dismissal of concerns about the law. Requiring a woman to travel to another state for care, perhaps by bus, is “not the worst thing in the world,” he said. It’s true—it would be worse to travel to another state and then you or your provider or the person who gave you a ride end up in explaining yourselves in court.

provided an analysis of why these attitudes are so enraging worth checking out.Not to mention, has New Yorker Mark Simone ever been to Arizona or looked at a map?

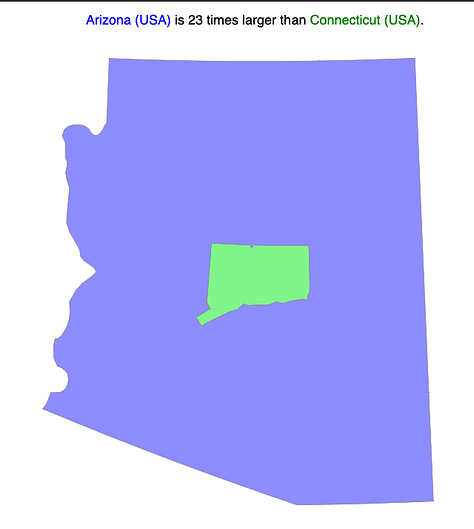

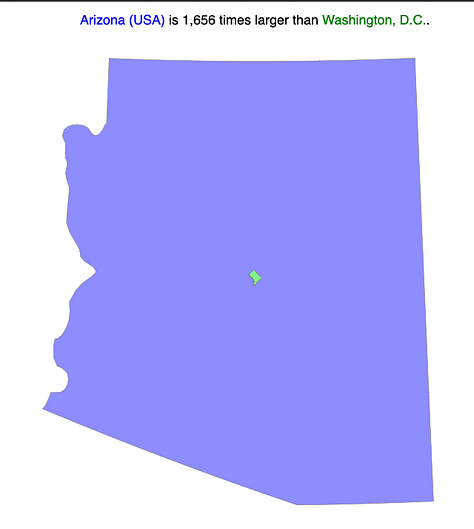

If you carved out an area the size of New York City from Arizona on January 1 and then did it again every day following, you’d finish January 10—of next year. If you begin at midnight and every hour you remove an area the size of Connecticut, a state with 8 more major highways than Arizona has, you’ll finish at 11 p.m. We could fit an area the size of Washington D.C. up in here for each of the 1,656 times someone commented online on Simone’s bad toupee last week. This is a big state; even if a woman has money and time off from her job or schooling, and no kids or family members requiring her whereabouts for a few days, it’s not so easy to get to another one.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Booktender to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.